Amelia Himes Walker, an 1898 graduate of York Collegiate Institute, York College’s predecessor institution, fought for the right of women to vote during the suffrage movement in the early twentieth century.

Amelia Himes Walker was born Amelia Eichelberger Himes on July 24, 1880, in New Oxford, Pennsylvania. She was the second oldest of six children and grew up in an affluent Quaker family.

Amelia attended York Collegiate Institute, York College’s predecessor institution, graduating in 1898. She then went on to attend Swarthmore College in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

At Swarthmore, she met both Alice Paul, a lifelong friend and leading figure in the suffrage movement, and her future husband, Robert Walker. Amelia pledged the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority and graduated in 1902, going on to marry Walker on June 11, 1910, at her childhood home.

Robert and Amelia had three children together—Talbott, Katherine “Kitty,” and Cooper. They raised the children at Robert’s parents’ home, Drumquhazel, in Towson, Maryland. The Walkers’s home was often filled with visitors, including musicians, actors, and suffragists. One of those suffragists was Edith Hooker, a close friend of Amelia’s.

While Robert worked as a life insurance agent, Amelia kept busy by becoming involved with charitable causes, many of them Quaker-affiliated. But her passion for women’s suffrage was growing. During her time as a student at Swarthmore, she authored an article urging for the passage of an Equal Rights Amendment, titled “Equal Rights?” It appeared in The Key, Kappa Kappa Gamma’s publication. As a young wife, she joined the Just Government Equal Suffrage League of Maryland.

Following her growing interest in suffrage and women’s rights, Amelia soon joined the National Women’s Party, a political organization dedicated to securing the passage of women’s right to vote, which was headed by her lifelong friend Alice Paul and cofounder Lucy Burns. Paul had kind words to say about Amelia:

“Her name was Amelia Himes when I knew her, a Swarthmore girl. She married a Robert Walker. She was a Quaker of course. She was a senior when I was a freshman and the loveliest person. I remember being in a Shakespearean play—by that time we were having these things at Swarthmore—and she was Ophelia, and I still can remember her being so beautiful and such a lovely voice and singing so wonderfully. So when we went to Washington, she was one of the people who had married over in Baltimore, and she joined in our committee and later became our national chairman, I believe, of the Women's Party.”

The National Women’s Party used strategies including protesting, marching, and picketing to make their arguments. These strategies were informed from Paul and Burns’s time in England. They had observed the more aggressive style of suffrage protests there and brought them to America.

On January 10, 1917, the group, along with other suffragists, had begun picketing the White House, after a delegation of women from across the country had failed to convince President Woodrow Wilson to support suffragists’ efforts the previous day. Wilson was steadfast in his belief that the issue of women’s voting rights was not a federal one, but one for the states. So these women, including Amelia Himes Walker and nicknamed the “Silent Sentinels,” staked out a daily picket line to pressure the President for his support.

Mobs formed at the site of the protests, causing unrest, and police quickly started to arrest suffragists. Amelia was arrested on July 14, 1917, Bastille Day, with the charge of “obstructing traffic.” Her good friend Edith Hooker was also arrested. Picketers were allowed to pay fines instead of jail time, but to draw attention to the issue of suffrage, the suffragists would often choose jail time over the fines. Robert Walker attempted to pay the $25 fine in lieu of sentencing, but Amelia chose to serve a jail sentence and was sentenced to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse, a prison near Washington, D.C.

The prison quickly gained attention for reports of abuse and poor living conditions, and after three days and “immense public outcry,” Amelia and the other women arrested on July 14 were unconditionally pardoned by President Wilson. However, they refused the pardon and resolved to complete their sentence.

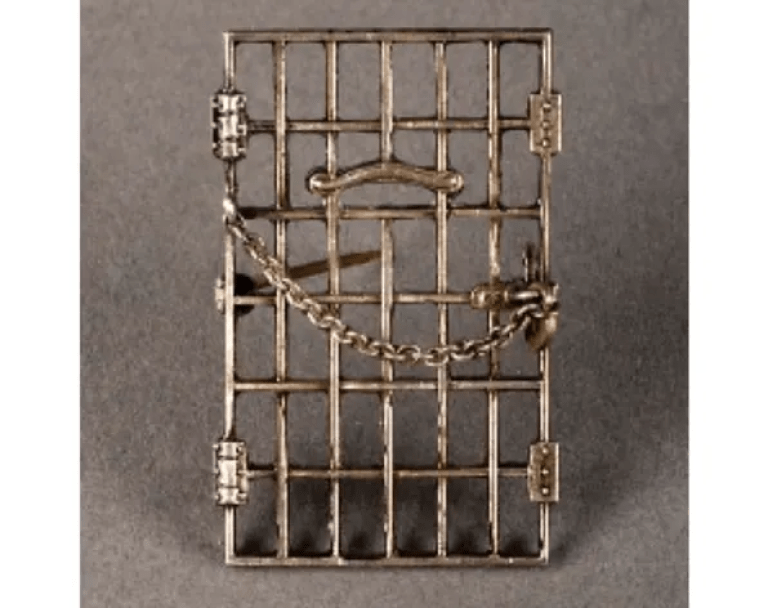

After the Night of Terror, in which suffragists imprisoned in the Occoquan Workhouse were brutalized, force-fed and left freezing, all the suffragists were released from the prison in December. That same month, a ceremony was held for all of the suffragists who had been imprisoned in the workhouse, and they were all given small silver pins made to look like prison doors to commend their bravery. Amelia donated hers to the Smithsonian Institution, where it can still be viewed today.

After President Wilson declared his support for women’s suffrage on a federal level on January 9, 1918, support for women’s right to vote grew. That same year, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the suffragists’ imprisonment and the abuse they faced was unconstitutional. In August 1920, the 19th Amendment was passed, giving women the right to vote.

Amelia remained active in women’s rights throughout her life. She served the role of president of the Maryland branch of the National Women’s Party, and was also an avid supporter of the Equal Rights Act, despite its failure to make it through Congress. She became the first woman from Baltimore County to run for the Maryland House of Delegates, seeking to address discrimination against women if she had won.

She later moved to Winter Park, Florida, after the death of her husband Robert in 1948. She didn’t let age her (80) stop her from traveling around the world and visiting such places as Egypt and Thailand. She was proud of having served jail time for the right to vote, often wearing her pin at National Women’s Party gatherings and other events.

Amelia passed away on July 19, 1974, at the age of 93. Her work in securing support for women’s right to vote made a lasting mark on history, one all Americans still benefit from today.